Tools For Cutting, Bending, Piercing, and Affixing Metal

Creating artwork from wire and thin sheet metal can be done with simple, readily available tools. The best tools are ones that are made to be strong and accurate. Quality tools can last a lifetime, and cost is a factor in determining the quality of a tool. Typically, better tools are more expensive. For example, an 8" pair of needle nose pliers can be purchased for under $3 at an import store, and it will last and work like a $3 pair of pliers (not very well, and not very long). Whereas a 6" pair of needle nose pliers by a quality company can cost in the mid-$20s. Professional specialty versions — for example, a pair specifically for electricians — can run more than $50. The cheap pair of needle nose pliers' jaws may bend under a lot of force, a jaw may snap off, the pivot may be difficult to move or it may be too loose, or the serrated teeth may wear smooth. A cheap pair's jaws may be out of alignment from the start, and the cutter might get damaged after first use.

Many unique projects require the use of tools that are available in the sculpture shop, but when this class is taught online, it is necessary to acquire some tools for yourself. Regardless of access to the classroom, I recommend that you buy these tools for three reasons:

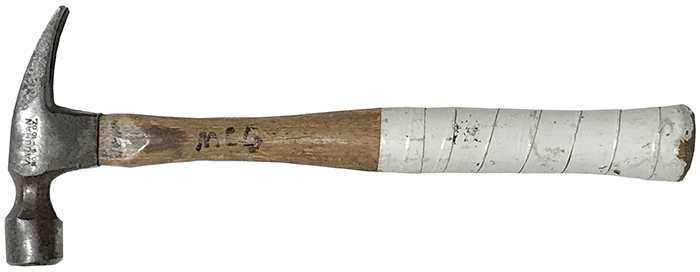

The sculpture shop only has the cheapest hand tools because of budget; plus good tools tend to disappear. You may wish to work at home on the project or to not have to share resources with other students. These tools are useful, and should be accessible throughout your life. The types of tools described below include those capable of cutting and bending wire, making holes in sheet metal, and cutting sheet metal. There are a number of ways to do all of these, and consequently there are a variety of possible tools to accomplish the project. A student could successfully complete the project with the most minimal set of tools: a pair of needle nose pliers, scissors, a nail and hammer, and a block of wood to hammer against. A piece of sandpaper could be used to clean up edges of sharp metal.

As you are shown demonstrations and read the descriptions below, it will become apparent that a larger set of tools can make the work easier. It is up to you to attain whatever set of tools you are comfortable with. Mine includes an entire personal studio of tools to choose from. All images on this page show tools in my own collection.

Awls, Punches, Nails, and Drills

Putting a hole in sheet metal is a simple process, depending on the thickness and metal hardness. You can do this in a variety of ways such as piercing, drilling or shearing.

Piercing

An awl is a punch that is used for soft materials where only palm pressure is needed to pierce. Because it is sharp, an awl can also be used to scratch or mark out lines, even on metal.

Besides an awl, a nail or a center punch can be used to pierce metal. Piercing is to push a tool through the material, displacing, rather than removing, material. Piercing a hole through 32 GA aluminum flashing (0.008" thickness) is very easy, even with palm pressure using an awl. However, doing the same for 27 GA galvanized steel (0.02" thickness) is nearly impossible.

The tool in the image, above, is by "Proto". It is a high quality center punch. Below it is an 8D nail. Both can pierce soft and thin aluminum sheets. The center punch can also pierce thicker metals. The block of wood is used to back up the sheet to be punched. The wood will give under pressure and not damage the tools. If a metal surface replaced the block of wood, damage could occur to the punch or nail. A hammer delivers the blow to tools that are intended to be struck.

A center punch with a good point, struck with a hammer, can easily pierce the aluminum and galvanized steel sheets described earlier. The sheet metal to be pierced should be placed on a rigid but soft material, such as a block of wood or an unwanted old book. If your house still has an old phone book, this is a great way to repurpose it before recycling. The wood or dense paper can support the metal while also allowing its surface to give under the punches' pressure. Care must be taken to protect your eyes, as the punch and hammer are both hardened steels that have the potential to shatter if abused. Note: I have shattered the tip end of punches before, though only a few times in 40 years.

Conceptually, a sharp nail is similar to a punch in that it has a striking end and a point end. A stout enough nail can be used as a punch, but it is not a hardened tool steel, and thus can bend or become dull if used on a hard or thick enough material. Though a nail may bend, it will not shatter, because the material is malleable (see definitions in the section, "A Little on the Properties of Steel").

Drilling

As sheet metal thickness and hardness goes up, punching becomes difficult. Other methods, such as drilling, will need to be used to make a hole in sheets heavier than flashing. Drilling is a subtractive process, meaning that material is removed.

A drill bit for metal consists of the cutting tip, the auger, and the shaft. The auger is the corkscrew-like form on the bit, and is for the removal of cut debris. As the sharpened tip cuts into the material, it peels or chips the waste, which travels up the auger, and out of the hole. The shaft of the bit is what is secured into the drill chuck.

Drill bits can put a hole through any thickness of metal, relying only on the bit length and strength.

A drill bit can penetrate thin metal sheets, but care must be taken to avoid catching the sheet into the augers and lifting it off of the support block. In this case, light cutting pressure results in much better holes than when heavy pressure is applied. When drilling through sheet metal, it is important to use a backing block, as described in the section on piercing.

A battery operated drill can be used to drill holes through sheet metal. The two bits shown correspond to the available wire gauges. One is 1/16" and the other is 1/8". This particular drill's chuck is capable of gripping 1/16" through 1/2" diameter drill bits.

Shearing

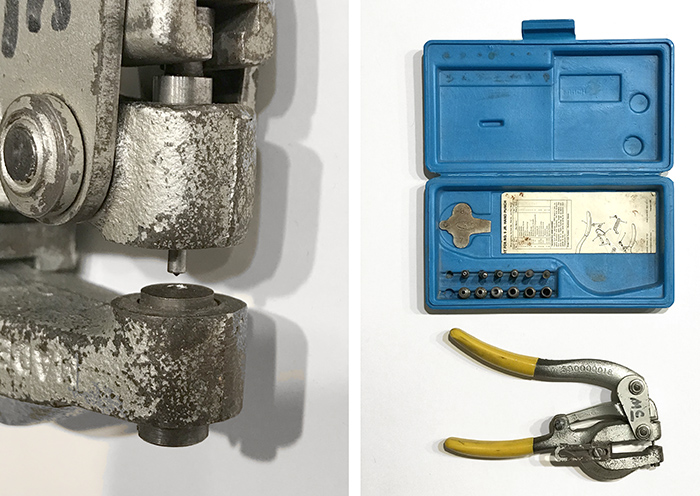

One last method of making holes in thin sheet metal is to use a handheld punch and die set. This tool is only useful in thin materials because it is squeezed like pliers. There is a punch and a die that work together to shear a hole through the metal. This is a specialized tool, not common in the home.

The tool typically comes in a kit with interchangeable punches and matching dies. It is critical to both the function and durability of the tool that only matching parts are used. If a punch is inserted that is bigger than the die, they both will become damaged.

When the tool is squeezed, the punch lowers with strong downward force, and the edges of the punch and die cut like a circular pair of scissors, shearing the metal, and creating the desired hole. The waste material is ejected out the bottom of the die end.

The tool's handles perform an arcing movement similar to pliers and scissors, but the punch makes a linear motion straight up and down. This complex, compound action gives a tremendous mechanical advantage of about 30:1. It is effortless to punch through aluminum flashing, and even galvanized steel.

A sheet metal punch and die kit is capable of creating holes in a variety of diameters. Shown on the left is a closeup of the nose of the tool. The punch is the pin-like portion, and the barrel-like portion is the matching die. The punch end must protrude above the die when the tool is open, allowing sheet metal to fit between them. When the tool is squeezed shut, the punch penetrates the metal, pushing the waste into the die opening. The punch must travel all the way into the die opening to complete the shearing process. If the wrong parts are used, a too-large punch can destroy both itself and the die by trying to force it's way into the too-narrow aperture. The mechanical advantage that allows for easily punching through sheet metal will also lead to easily damaging the tool if used improperly.

Tin Snips, Aircraft Shears, Scissors and Craft Knife

Sheet metal cannot be cut with diagonal cutters and end nippers because those tools do not shear; they crush. To cut through wide and long materials, a shearing action is needed. There are lots of tools that make a shearing action, including the punch and die kit mentioned earlier. In this section, cutting tools that work with a scissoring action are described, along with a knife tool that can only be used in a specific instance.

Cutting tools come in a huge range of shapes and sizes depending upon function and design innovation.

Tin Snips

Tin snips are very closely related to scissors in that there are two blades that pass by one another to make a shearing cut, there is a fulcrum, and there are handles. They differ in the robustness and shortness of the jaws, and the heaviness and length of the handles. There are also more subtle differences in the grind angle of the blades. Tin snips are duller than scissors, because if they were sharpened too much they would immediately dull anyway. There is tremendous mechanical advantage in both the lengths and stiffness in tin snips. Just as with pliers and nippers, the area closest to the fulcrum applies the most force. Thicker and harder sheet metals can more easily be cut in the deepest part of the blades. The tin snips shown can easily cut curves out of metal using the right techniques.

Aircraft Shears

Aircraft Shears, or aviation snips, are compound action, which increases their mechanical advantage, effectively lengthening the handles by folding the motion into a smaller space. These tools were designed for the aviation industry to work with aluminum. Because of the power of these tools, they are easier to use than tin snips when cutting thicker and harder metals. Although there is mechanical advantage, they have several disadvantages over tin snips:

Because so much force can be applied, it is easier to damage the blades when misusing. The flat bearing area for the fulcrum is relatively small, making misalignment possible when shearing. The shape of the jaws make using a pair for all types of cuts difficult, thus there are multiple types needed: straight cut, left cut, and right cut, to name three. Often the blades are serrated, leaving a rough edge on the cut metal.

Scissors

Common household scissors cut paper and other soft materials beautifully. They are also well-suited for thin aluminum flashing. They are not appropriate for cutting harder and thicker metals. Scissors have longer blades and shorter handles, limiting their mechanical advantage over tin snips and aircraft shears. However, they are comfortable to use, readily available, and can easily cut soft metal to curves and straights. It is important to know the physical limits of scissors, as it is possible to break the handles off if too much force is applied. Plus, the blades will become quickly nicked or dulled by hard materials. Never use scissors to cut wires, as many wires are hardened a bit, and round, which can leave rounded nicks in the blade, making the scissors a very poor tool, even for cutting paper.

Craft Knife

The most unlikely tool for cutting sheet metal is a craft knife. It is not capable of cutting all the way through even 32 GA aluminum flashing. But the flashing has an interesting property. If the flashing is hard enough, scoring a line with the knife will allow the aluminum flashing to tear on the line with great accuracy. This will not work on galvanized steel. If the aluminum is dead soft, the tearing or splitting property will be lost.

Scored aluminum is a common feature of pet food and soda cans. These cans rip open directly on the pre-scored seams that trace the desired opening. The appropriate downward pressure on the lid of the soda can, applied by hand with the built-in tab, starts the ripping process, and is safe enough to allow someone to drink out of the opening. The edges are still sharp, however.

Needle Nose and Lineman's Pliers

When working with wire, it's important to have a tool that you can easily hold in one hand, and that allows you to bend wire with a good deal of force. Plying means to do work with something; thus the name "pliers".

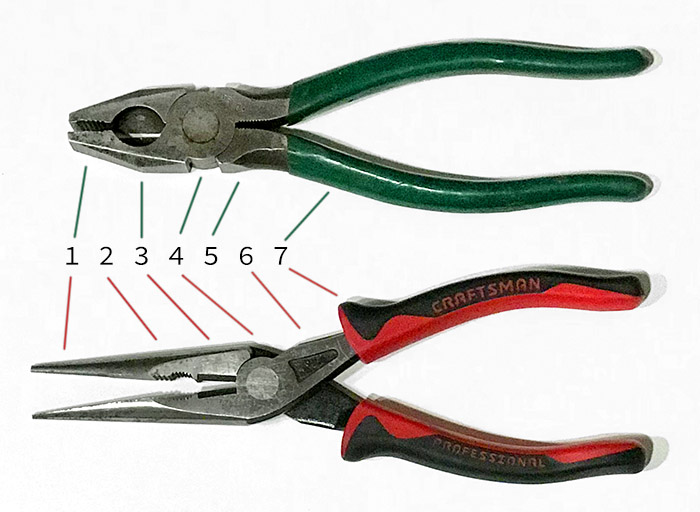

Pliers come in a lot of varieties, but one type is an essential tool for wire work: needle-nose pliers. The jaws project to a small tip that make it possible to bend fine loops. Because the jaws are elongated, the tips have far less mechanical advantage over pliers that have short jaws, but as long as the wire is pliable enough, the tool will have enough leverage. There are specialized pliers with very short jaws that come to small tapers, which increase mechanical advantage.

Lineman's pliers contrast with needle-nose in that the jaws are wide and short. They have tremendous grip, but because of the wide jaws have a difficult time bending fine loops. They are handy for holding wires when twisting, compressing, and pulling.

The two pliers together make it possible to do more intense work to wires. This is useful when holding the raw wire in your bare hand becomes difficult or painful.

Here is a list of the pliers features:

Serrated Jaws. Some pliers have smooth jaws. The former grips very well, but leaves marks, while the latter leaves less damage, but may allow slippage while plying. Pipe grip. This feature is available on many styles of pliers. Cutter. The cutter is very close to the pivot for leverage, and can cut wire. Pivot or Fulcrum. Inner Serrated Jaws. Because the jaws are so close to the fulcrum, it has high mechanical advantage. The black areas of the needle-nose pliers indicate that it is most likely cast, because the surface finish is textured like a sand casting. Handles. They both have rubberized grips for comfort and a secure hold. The needle-nose grip is injection molded and contoured for better hand-feel. The lineman's pliers was dipped in liquid rubber.

End Nippers and Diagonal Cutters

Although many pliers have diagonal cutters built into them, it is often handy to have a separate pair of cutters that are dedicated to the task. For one, you may be holding a piece of wire with the pliers while needing to nip the wire short. More commonly, you may need to nip with a tool that can cut at the tip of its jaws rather than deep inside the jaws. Parallel and diagonal cutters' blades run all the way to the end of the jaws.

Diagonal cutters are the most common, and have mechanical advantages for nipping over parallel cutters. The blades run from just outside of the pivot all the way to the end. If you wish to increase cutting pressure, the wire can be cut close to the pivot. If it is necessary to use the tip of blades to nip wire, the jaws are usually short enough to still apply a lot of force. Here is an example of how mechanical advantage works on diagonal cutters: The cutter travels 3x distance at the tip, and 1x distance at the inside. That means the inside of the cutter applies three times the force as the tip; conversely, the tip of the cutter applies 1/3 of the force as the inside.

Parallel jaw cutters, or end nippers, are useful when you need to remove a pin or nail from a material because it can grip well — if not too much squeezing force is applied — and can act like a gripping pry bar to extract the item. It can also cut close to a surface across its face. Diagonal cutters can also cut close to the surface, as long as there is nothing in the way of the handles to block access. End nippers have only one level of force applied all across the blades, meaning there is no place on the jaw where an increase or decrease of pressure can be applied.

The fixed pressure of this design is due to the fact that the anvil edges are always equidistant from the pivot radius.

Sand Paper and Files

Ends of wires and edges of sheet metal can be very sharp, especially after cutting. They can also have burrs, which is a common property of sheared, punched, drilled, and nipped metals. Burrs are caused by micro folding of the edge on the tiniest scale because the material is soft and malleable at that scale. The metal forms a crested wave that acts like a blade or scraper. It is possible to cut yourself on the burr, plus it looks and feels rough.

A burr will not take paint finishes well because paint, being a fluid, has surface tension, and sharp edges stop the fluid in its tracks. A refined and radiused edge on metal will take paint beautifully, as the surface tension will cause the paint to flow around the edge. Painted metals with rough edges will deteriorate much faster than those with smooth edges.

Sand paper

Sand paper is either a paper or fabric mesh with graded, very hard particles glued to one side. It is made from a wide variety of minerals and compounds, selected for their hardness and sharpness. These minerals, such as garnet, aluminum oxide, silicon carbide, and ceramics are significantly harder than metals, which is why they can be used to work the surface. The qualities that make sand paper so valuable are its flexibility, evenness of grit, hardness, durability both in holding sharp particles, and the ability to prevent clogging with swarf.

Swarf are the particles removed during sanding, filing, and machining.

For this project, many different grades and qualities of sand paper will work well, as long as they are coarse enough to roughen the surface, and fine enough to round over sharp edges and remove burrs. You will be working with aluminum, which is easy to sand. High quality sandpaper can work well under water or when wet. Poor quality sandpaper will fall apart under these conditions. Working wet helps remove swarf before it can foul the sand paper or prevent further sanding with debris. Also, high quality sandpaper particles stay sharp by fracturing when damaged, rather than rounding over. These fractured particles still have cutting capability.

I suggest using sandpaper in the range of 180 to 320 grit. In general, you can consider the grit number to mean the number of particles that would line up in an inch, if side by side. This gives you a visual of how different particle sizes compare. In reality, the particles in any grit range vary a little, and are graded by mesh screening.

Files

Another tool that can be used to remove burrs and round over edges is a file. There are as many file types as there are pliers, nippers, shears, and any other hand tool category. They are specialized for specific purposes. Some are very coarse, others are super fine. One kind has a single series of parallel cuts in the surface, while another has double cuts. The cut angles vary, as can the shear angle of the individual tooth. Files range from short to long, flat, round, half-round, triangular, square, rough on all edges or smooth on a side. . . the subject is huge.

For projects using aluminum sheet metal and steel wire, a simple set of rules can be followed to find a good file for the task. The goal is to use a file that can easily and cleanly remove burrs and to radius (round over) sheet metal edges. It should be able to refine bumps and to take sharp points off of wires. All of this can be achieved by using a single-cut bastard file with a fine tooth, as shown in the example photo.

I recommend about 50 teeth per inch. If a file is too coarse, it will chatter, and if it has double cuts, it will more likely leave small scratches on the filed surfaces. Files that are micro-fine will clog easily..

The best shape and length for a file (if it is the only one you will own) is a 6" to 8" half-round — because it can be useful on both convex and concave edges. This size will be useful for many things. Files come in a tremendous range of sizes and shapes, and this can be overwhelming. Many different sizes, coarsenesses, and shapes can substitute for one-another, though files seleceted with specific properties for a specific task can make the job easier and the results better.