Module Proportion and Shape

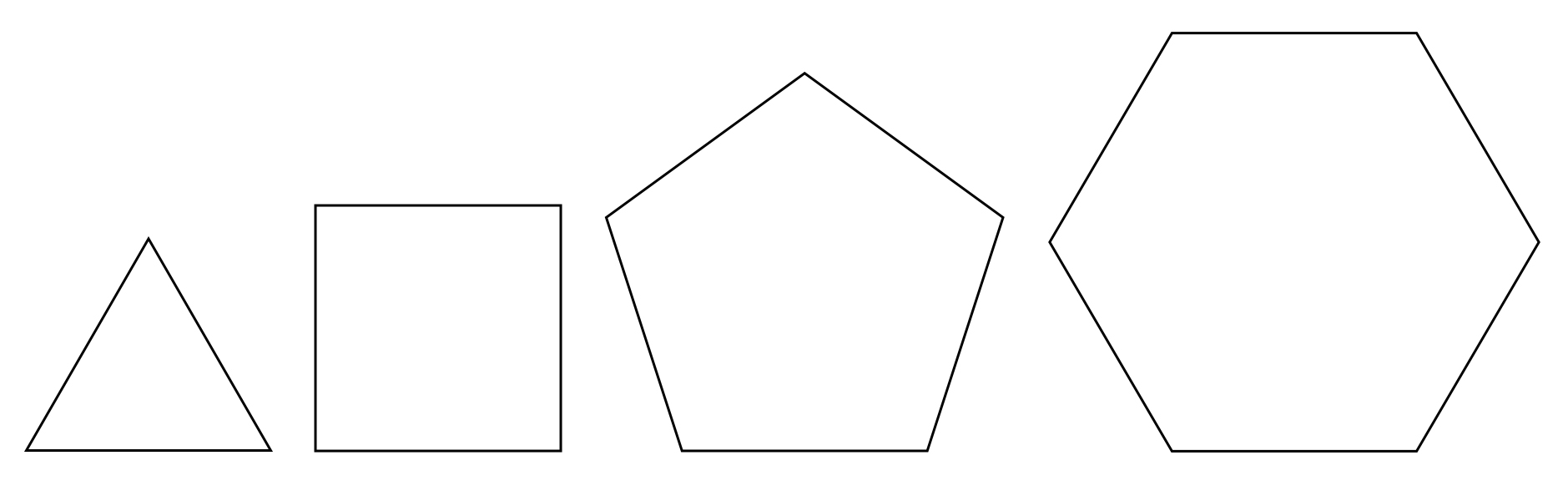

There are essentially three classes of shapes that make up the basic polygon: regular polygons, irregular polygons, and creased or folded polygons. The latter is present when your design contains concave dihedral angles, and as soon as you fold them, they are no longer defined as polygons anymore. Some of the regular polygons are shown above. There is an infinite number of them, but only a select few will form a complete enclosure without adding irregular polygons as well. From a mathematical point of view creased or folded polygons can stare out as either regular or irregular polygons.

Basic Polygon Surface Area and Edge Length Relationship

Adjacent modules must mate edges, meaning the edge lengths of all adjoined polygons must be the same length. If they are regular polygons, then there are fixed proportions. The surface area of each type of polygon varies, as seen above.

If you wish to create a lamp where the relative size of the modules look similar, the types of polyhedra are limited. Notice that any two unique polygons are more similar in size to the ones next to them. Triangles and squares are close in area, as are squares and pentagons. Pentagons and hexagons also work well proportionally. The further away these shapes are from one-another in the above image, the greater the disparity in surface area.

Other polygonal relationships can also work well in a lamp design, as long as the extensions help the scale feel right. Triangles and pentagons have a larger proportional difference, as do squares and hexagons. But the biggest difference is between triangles and hexagons. In this last case, the hexagon is quite dominating.

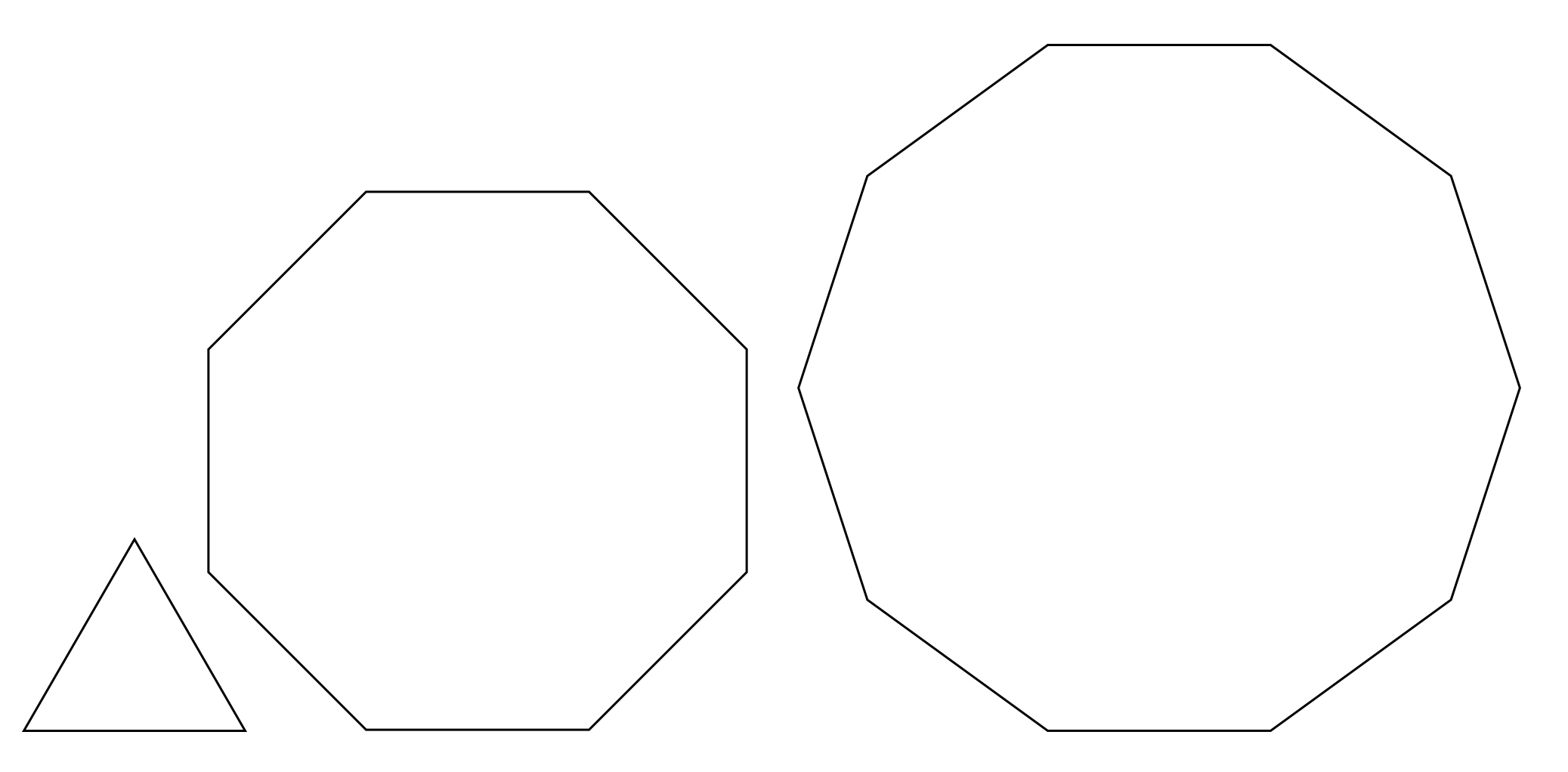

The case gets much more extreme when other regular polygons are employed, such as triangles and octagons or decagons, which can occur in partially truncated cubes and dodecahedrons. Below are some of these examples.

Extension Proportions

The extensions exist for two reasons. One is mechanical, allowing for an interlock between modules. The other is aesthetic, which means there is a lot of leeway in regard to shape and size. That said, there are certain limitations that should be considered. For example, if they are too small, they may not have enough structure to interlock strongly with its mate. Also, small extensions cause a large portion of the basic polygon to show.

One design goal is to make the extensions at the least as important visually as the base polygon. This does not mean they need to be large, just interesting enough to compete. If they are large in relation to the polygon it overlaps, they must relate to the other extensions that also overlap the polygon from its other edges.

It is possible to design extensions that when assembled as a whole completely obscure the basic polygon.

When a lamp is created from a Platonic solid, all modules are identical, thus the extensions must relate in size to its own base polygon. In some cases, though. a lamp is created from an Archimedean solid consisting of at least two basic polygons. For example, a truncated cuboctahedron is made from 12 squares, 8 hexagons, and 6 octagons. Each square mates with two hexagons and octagons, etc. So in this case, two extensions of the square have to relate to hexagon size and two to octagon size. A more dramatic relationship is found with the hexagon, which as to interact with three squares and three octagons. The octagonal shape is gigantic compared to the square.