Shadow Layering

An important element of the Lamp Project is shadow layering, which occurs naturally. This is an intrinsic design criteria that must be considered and manipulated, as it transforms the simple underlying polyhedron into something incredible. Typically, this effect is created by allowing the extensions to pass through one-another, then project out in space. As the extensions move away and out, above the surface of the enclosure, the tonality of their surface grows darker. If the design is circumvolved, returning portions of the extensions grow lighter as they approach the enclosed polyhedron. When extensions begin to overlap one another, they create complex and layered tonal differences.

Unlike the more common designs, the lamps shown on this page focus on the shadow layering effect being applied to the flat surfaces of the polygons, rather than projecting out in space.

Inner Projection

The lamp, above, achieves a clean, two-tone effect. The floral patterns are soft along the edges because the cut-out windows that define them are behind a solid outer shell. If the layering was reversed, and the cutouts were on the outside, the floral pattern would appear sharp.

Outer Shading

Here, the spiralling tonal pattern was created by interconnecting five layers at the center. The center pentagonal pinwheels are the only interlocks in this entire lamp design. This lamp is not made out of pentagons at all, rather, the modules are "S"-shaped. They are bent at their centers to form the dihedral angle of the dodecahedron. Typically, a lamp that uses a dodecahedron has 12 modules. This one has 30 because there are 30 edges in a dodecahedron. The effect of creating a design like this is that the lightest part of the lamp is at the edges, the reverse of a more typical design.

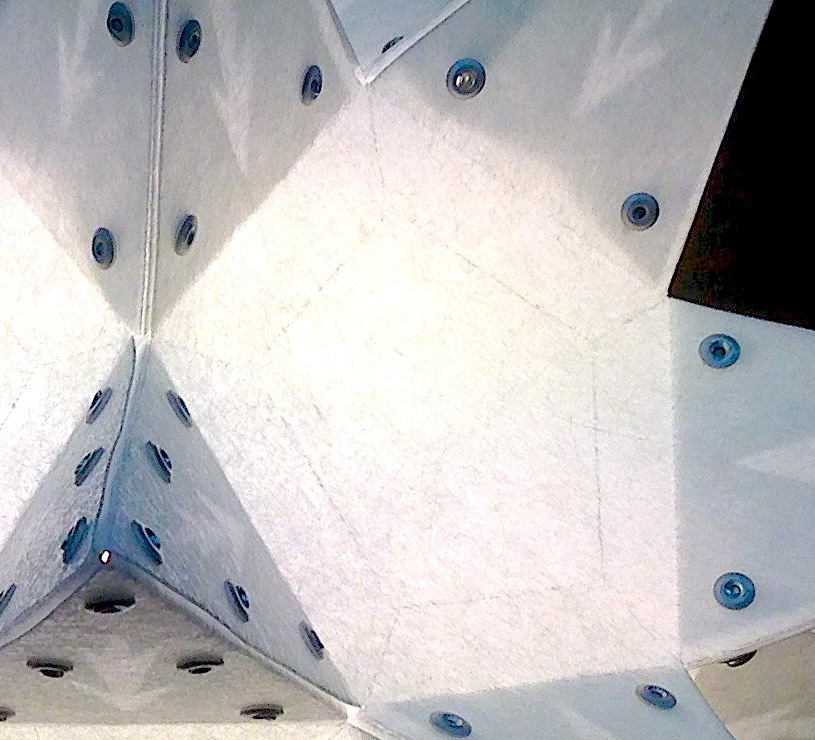

Utilizing Enclosed Stellations

Enclosed tall stellations naturally have light fall-off as the stellations move away from the core. This follows the rule of squares, where the amount of light hitting a surface at twice the distance of anorher is 1/4th as bright. This is used to dramatic effect in the lamp, above. The stellations are actually made from two layers of material that are riveted together, doubling the tonal shift. The underlying layers in the stellations have the arrow-shaped cutouts in them.

It is difficult to know what the actual module's shapes are, but it is safe to say that they are identical, complex and well thought out.

There is another, almost hidden element of attachment that is in plain sight but nearly invisible: the stellations have sizable tabs on them that are glued to the bright pentagons. The joint is hard to detect, despite the fact that there are two layers overlapping there. You might expect to see a dramatic tonal shift where these two layers attach, but you don't because they were glued with a colorless transparent adhesive. This adhesive breaks the normal light barrier that occurs on both sides of the lamp material that face each other, and allows the light to transfer to the second outer surface, as though only one thickness is present.

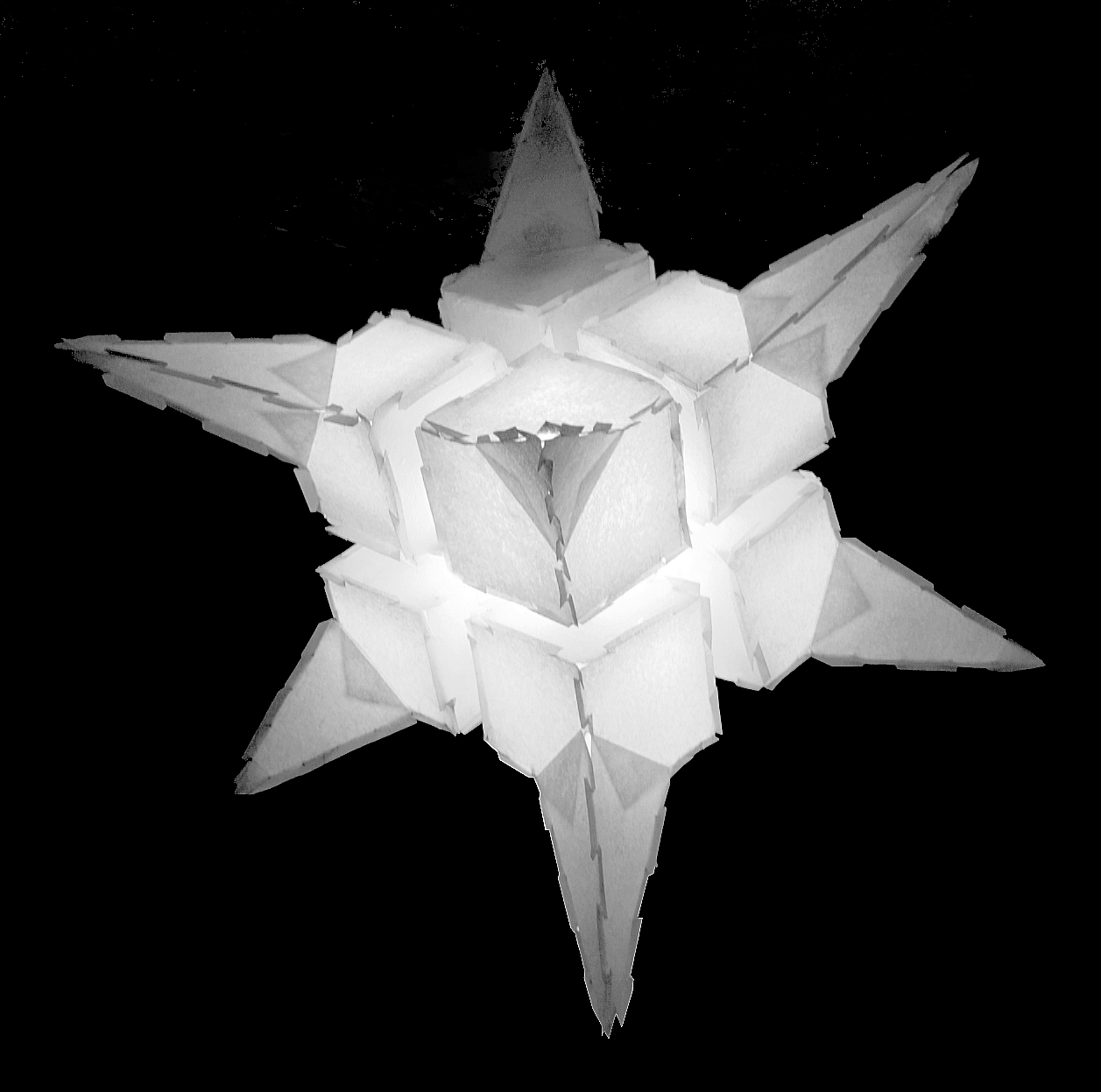

...And Notches

Like the previous lamp, the lamp, above, also uses stellations for tonal variation. It further incorporates notches in the cubic surface. These notches are the brightest parts of the lamp, making the object feel like it is white-hot and solid. This design utilizes an interesting dovetail-shaped series of interlocks running along the edges. The stellations are glued to the truncated cubes, and tabs attaching them to the cubes can be seen as triangles through the stellations. Those triangle tabs are the remnants of the corners of the cubes, which is why they are 45°-45°-90°.