Examples of a Singular Sculptural Object

"In my opinion, everything, every shape, every bit of natural form, animals, people, pebbles, shells, anything you like are all things that can help you to make a sculpture," Moore said of his work. "The observation of nature is part of an artist's life, it enlarges his form (and) knowledge, keeps him fresh and from working only by formula, and feeds inspiration." (Quote attribution: Henry Moore From the Inside Out : Plasters, Carvings and Drawings (ed. 1996))

THE ARCH, by Henry Moore, is a monumental sculpture that has been made in various materials including bronze and travertine marble. The stone piece was carved from several assembled sections that were bonded together. The bronze piece was cast in parts, and welded together. The version shown here was fabricated in fiberglass, as it was originally exhibited in a location that could not take a heavy load. The processes for working each type of material varied radically.

Moore was an advocate for "truth to materials", which means that the natural properties of a material are allowed to come through the work. This concept was realized by many of the artists on this page. However, it is notable that the above version of THE ARCH is not true to its material, and that many people believe it is made from marble.

The artist was fascinated by Stonehenge and other Neolithic structures that contained arches made of stone columns and balanced beams. In this sculpture there appears to be references to such man-made structures, as well as bones and tree forms.

The scale texture, form, and materiality of the work is able to complete and integrate beautifully with the scene around it. The rough surface textures are meant to reveal the hand of the maker, where tooling marks are celebrated. However, because of the scale of THE ARCH, it's textures are contrived since they had to be reproduced to mimic the actual tool marks found in the maquette. This does not diminish the power of the marks as they help humanize the work.

The above sculpture is small in comparison to Moore's monumental works. When he was at this early stage of his career, he thought that creating monumental sculpture was "silly", and only had an interest in creating small pieces. This changed when Moore was commissioned to make his first large work. His small marble sculpture has incised geometric elements that contrast with its outer, more curvilinear form. It has no cut-throughs; instead, the piece relies on hard shadow to give the work power. It evokes growing, weathering, and cutting.

"In 1931, (Moore) was denounced by the Morning Post for promoting ‘the cult of ugliness’, sparking a furore (sic) that cost him his teaching job at the Royal College of Art. His sin, in the eyes of traditionalists, had been to abandon the classical ideal of human beauty in favour of something earthier, chunkier and more ‘primitive’. (Quote from countrylife.co.uk)

Read more on The Henry Moore Foundation, this Sculpture Magazine article, and watch this short introductory video about the artist (made for children).

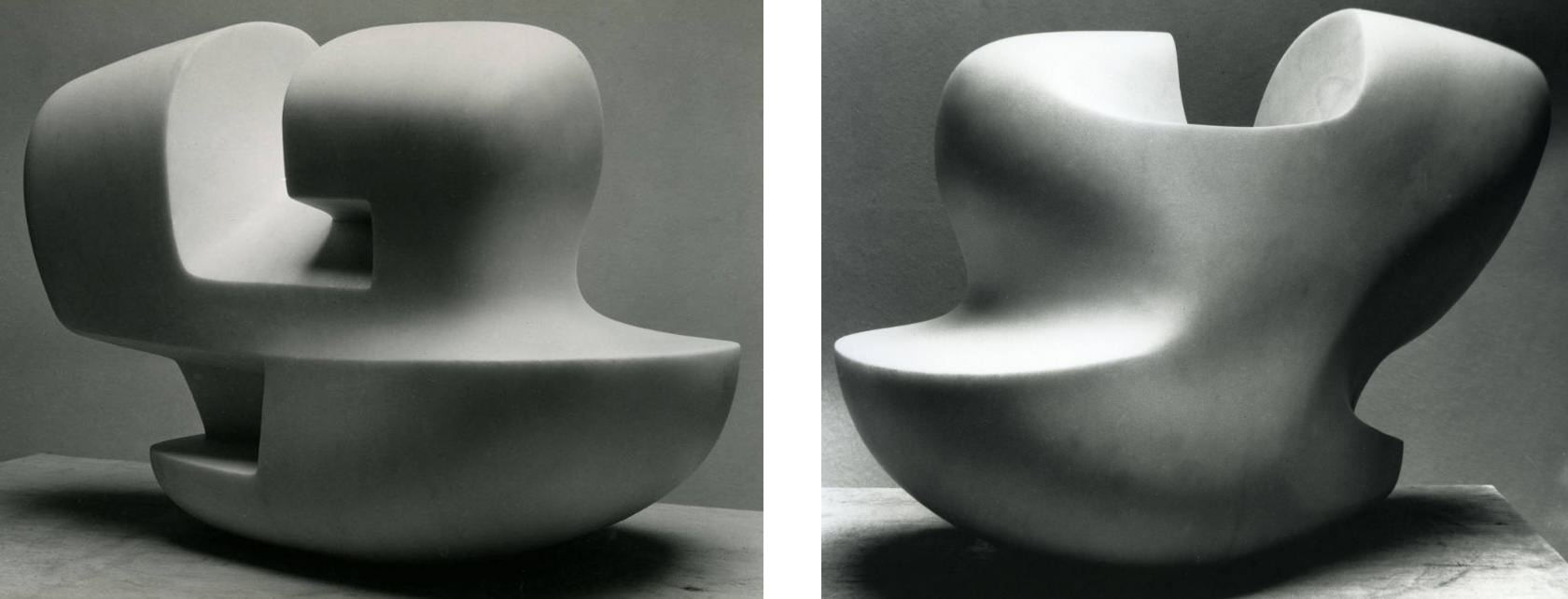

Above, smooth simple abstraction is present in CURVED FORM by Barbara Hepworth. She created a void with multiple openings that balance the work's clean outer surface. The inner penetrations create contrast through light and shadow, and presents a strong negative form, best viewed in a soft raking light. This elongated sculpture clearly has a front and back view.

Hepworth, as with Henry Moore, revisited sculptural concepts many times. OVAL SCULPTURE was reproduced in various media, each evoking a different feeling. The wood is warm and textured, the stone is pure and soft, and the bronze is complex and shiny.

In the left sculpture, the inner surfaces contrast the outer through the use of color and shadow, and the difference is striking; the two surface treatments create a tension at their shared edges as the outer warmth nests and defines the inner white. In the middle sculpture, the neutral tone and matte surface of marble allows the outside to describe its volume through natural tonal variation, which balances the complex inner light and shadow. And finally, the sculpture on the right creates very complex reflections that camouflage the actual surface contours of both the inside and outside.

OVAL SCULPTURE is striking in how the outer volume is described as a smooth, convex, egg-like form that can appears inflated, while the inner surfaces appear to stretched like a skin that is tensioned between openings.

In Hepworth's sculpture, HEAD (MYKONOS), a single hole is reinforced by the vortex or spiral that leads into it. The irregular spiral makes a transition from the outer perimeter to the clean circular hole that is carefully located just above center. This spiral is distorted by the flattened top of the sculpture. Defining features of this piece are its broken symmetry, and use of hard transitions between contours, which give it life. The carefully prepared satin finish gives the sculpture a gentle light and shadow tonality.

See more of this artist's work at barbarahepworth.org.uk. Watch this short video about Barbara Hepworth from the Tate.

Richard Erdman's PASSAGE is a complex interwoven sculpture that roots itself strongly to the ground by resting on four truncated feet. This solidity is contrasted by the sculpture's sweeping peaks that reach upward into the sky. There is the appearance of movement through the ribbon-like surfaces. The arches between the feet create visual and real passages, which are balanced by open arcs above them. The work is both weighty and delicate throughout, which is espcially true in the small gap formed by the overhanging projection. In the second image, the sculpture appears to be composed of two interwoven elements.

See more at richarderdman.com. Here is a video on the making of PASSAGE.

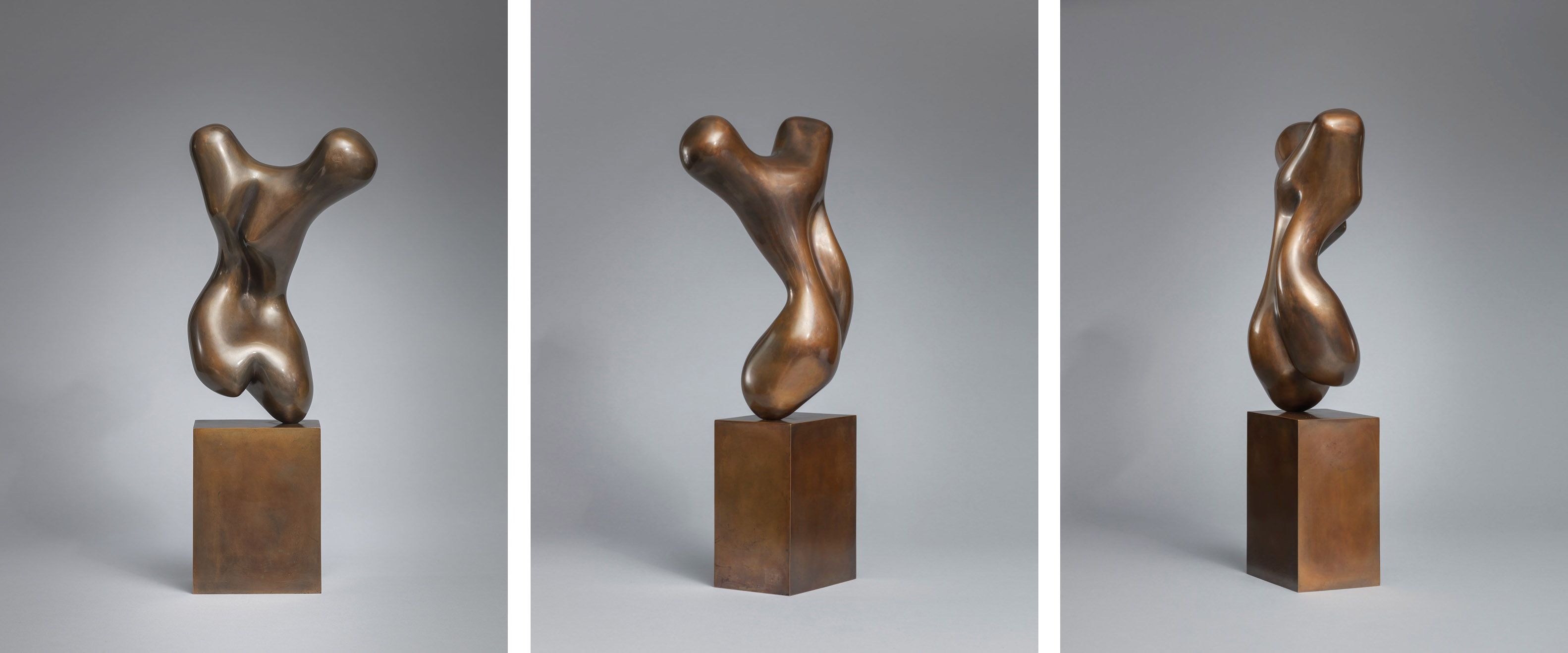

TORSE, by Jean Arp, is a figurative sculpture whose concave and convex forms relate to one another, yet are not duplicative in any way. The scale of each individual element is balanced, and the whole of the sculpture has the movement of a dancer in space. This is reinforced by how the piece is placed on the sculpture base; one single point on the piece is gently touching, which implies action and an energetic upwards gesture. Furthermore, the overall mass seems to be centered in space on the base from many vantage points around the sculpture.

Arp's piece has no sharp edges, other than those on the base. All transitions are smooth and soft. The terminus of each "appendage" is bulbous or organically rounded. All concave elements are likewise smoothed. The overall form evokes the bilateral symmetry of the human body, but is not actually bilateral because the torso is arced and twisting. This movement implies time.

Arp had many creative outlets besides sculpture, and he also worked in a variety of materials in sculpture, including plaster. Most of the time, plaster was used for record-keeping and for working out ideas, but it was sometimes the medium of choice. In the book, Ancient Plaster Casting Light on a Forgotten Sculptural Material, plaster is shown to have been an important medium to artists for millennia.

Read about Jean Arp on Wikipedia. See a video on Arp's work in plaster at the Nasher Sculpture Center.

While Rachel Whiteread's monumental sculpture, UNTITLED (STAIRS) does not contain the organic forms, arcs and voids that the rest of the sculptures on this page do, it is composed of elements that would naturally interlock with one-another. This piece feels both inside-out and rational at the same time. It is a casting that was made directly from the negative space that surrounded a real staircase - the stairwell was the mold - which was then removed to reveal this new form. The sculpture's orientation of 90-degrees from the expected adds to its confounding beauty. It takes effort to understand the original space that this piece describes.

Another aspect of Whiteread's sculpture is its massivness. The weighty, solid, and blocky feeling is the opposite of an open staricase, which normally feels light, airy, and delicate. The planar, slab surfaces define a space occupied by people who move through the stairwell over time. Finally, the object goes nowhere and cannot be accessed - antithetical to the intention of a staircase.

Read more about Rachel Whiteread at britannica.com. Video: Who is Rachel Whiteread?. Video: Documentary: Rachel Whiteread, House (1993)