Differences between Compasses, Calipers, and Dividers

Compasses

Circles and arcs are fundamental elements of design. So is the accurate splitting of line segments, angles, or arcs. Compasses can do these tasks with ease. A compass can also be used to mark out repeated lengths. This basic tool has been innovated and manufactured in countless ways.

Conceptually, a compass (or more precisely, a drawing compass) is a tool that has a point end and a drawing end such that a circle can be drawn. This is done by placing the point end on a desired radius position, the drawing end at the desired circumference position, and rotating the compass about its radius, thereby tracing an arc. An extremely simple compass may be fixed, with no pivot or adjustment so that it only draws one size circle or arc. This would be useful in an environment where it is important to repeat only one measurement without fail. That is not how most compasses work though. Almost all compasses are adjustable. They are designed with either a tight or lockable pivot mechanism joining two individual arms, or with a sliding mechanism that clamps to a straight rod or beam. The solutions to those two mechanisms are vast, as is evidenced by the number of different designs sold around the world for centuries.

Innovation in compass design is the product of their incredible and basic usefulness in creating our built world. Only in recent times has the compass been supplanted by another tool: CAD (Computer Aided Design). Still, compasses are essential for anyone who makes physical objects by hand. Over the course of thousands of years, compasses have been fundamental in the work of architects, builders, fabricators, artists, graphic designers, engineers, mathematicians, scientists, map makers, and anyone with an interest in making accurate circles. Virtually every artist and renowned creator has relied on, and mastered, the compass.

About the Compasses Shown:

- A majority of the compasses shown are about 6" long and can draw a maximum circle between 10-12" dia.

- All compasses with the circular spring at the top and adjuster wheels in the middle are "Bow Compasses". The spring gives them their name. The adjuster wheel and their screw threads fix the compass to a given radius.

- All of the compasses with a pivot point and no spring or adjuster wheel are called "Regular Compasses". These are not as capable of precise adjustment because there is no wheel. Most lock in position with a thumb screw that slides along a slotted arc. These adjust very quickly.

- Some of the regular compasses have no locking thumb screw, and instead rely on inherent friction in the design.

- The largest regular compass (the one laying sideways) can draw a 36" dia. circle.

- There are three "Beam Compasses". They have no pivot points, and instead rely on a rail, or beam.

- The vertical beam compass on the far right and the short one on the bottom-right are only limited in diameter by their beam lengths, which can be changed.

- All three beam compasses shown have scales that read the radius.

- The red anodized aluminum trammels on the large beam compass were made by my friend, John deMarchi. Trammels are the parts that lock on to a beam to make a beam compass.

- With the exception of the small brass compass in the middle-right (4th over from the green compass), all of the metal compasses with pencils in them are made specifically for woodworking.

- There are three very poor quality compasses in the group for comparison: the safety compasses made of plastic are for children, and are terrible. The 6th from the left in the top row has a pen-cap and can fit in a pocket. It has no wheel adjuster and is not a serious tool.

Dividers

A divider is very similar to a compass, with the exception that there are steel points on the ends of both legs, as opposed to one leg having a graphite or inking nib. Both dividers and compasses can be used to do the same job, but the divider can only make an arc by scribing, or scratching a line. This is useful when drawing a very precise arc or circle on metal or other hard objects, or soft objects that cannot transfer graphite or ink. A divider is also used for measuring off of drawings, maps and other flat objects. It can be used to transfer measurements, and also for repeating lengths one after the other. As an example, you can set the divider to the 1-mile length on a paper map, then count how far it is along the road to another town. The points can further be used to prick the surface of paper for a dead-on mark.

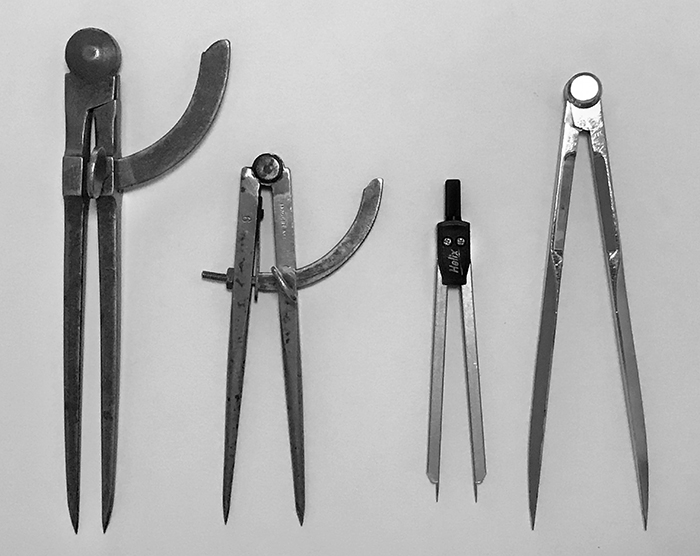

Shown above are four dividers, each with different characteristics. The two on the left can lock in position; the smaller one has a spring and nut for fine tuning the adjustment. The two on the right hold position through friction: smaller for drafting, larger for navigation.

Calipers

A variation of the divider is the caliper. These have curved legs if they are regular or bow. Beam calipers ride along a rail. The curved legs make it possible to measure the inside and outside of objects. Calipers can also be used for transferring measurements and for comparing two objects. They are common in ceramics and sculpture.

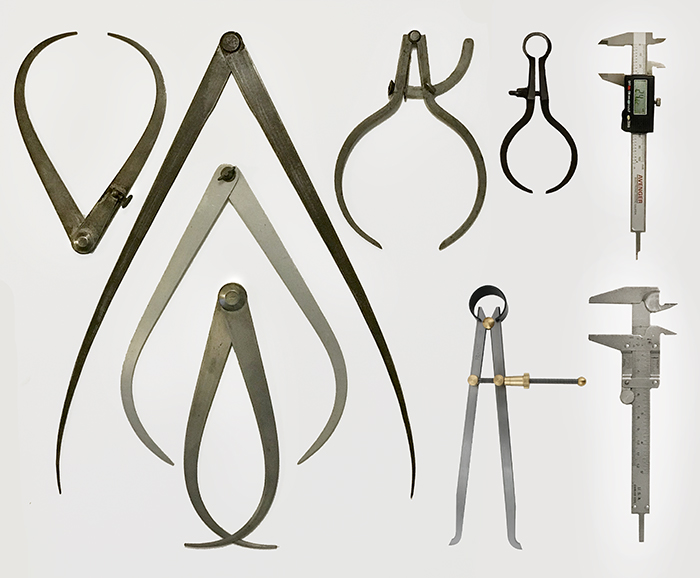

In the collection above, notice the similar features calipers have to dividers and compasses. Some hold with friction, others with threads and bow springs, and the two on the right clamp to beams. Of the beam compasses, the upper one is digital, and the lower one is Vernier. The beam calipers can measure inside, outside, and hole depth. Of the pivot calipers, all but one are for outside measurement. The one with a bow spring and a brass nut is an inside caliper. The three calipers with friction mechanisms can be closed so far in that they can be used to measure inside lenghts, though their curves make them less capable than a dedicated inside caliper, whose leg ends would curve like the inside caliper described earlier.

Modern Innovation

Because they are not used by architects and designers on a daily basis anymore, new high quality compasses are difficult to find. This does not stop the flow of new products, as designers are still fascinated with the tool and enjoy innovating. These innovations are not likely to succeed because of market forces. Here are a few of those, some high-concept, some real. Some are not actually compasses, but are still for drawing circles:

- CARBU, by Michael Dimou

- MAGCON, by Ddiin (the website is fun, so I linked to that. Find the MAGCON within the site)

- IRIS, by Makers Cabinet (for drawing circles, but not with a compass at all, based upon camera irises)

- GIHA WOO ELLIPSER (takes you to youtube, this one is for drawing ellipses, not circles)

- SS Compass (Woodpeckers OneTime-Tools, limited-edition, made only based upon pre-orders)

The last on the list (the link to Woodpeck) is a product specifically for woodworkers. The compasses are seen in the image at the top of this page; they have red pencils which can be swapped with scribing pins. They are made out of laser-cut flat stainless steel sheet, which is how the company can produce limited-edition tools for fanatics and collectors like me. Their lean 21st century manufacturing processes do not rely on tool and die making. This gives them the ability to rapidly shift products. These compasses have extremely smooth movement and are a pleasure to use.

Finding a Good Vintage Compass

Compasses have been made by quality companies for professionals throughout the 20th century. Only since the wide adoption of computers for design, architecture, and engineering have these companies begun to disappear or shift to other products. Sadly, a large number of these companies' current offerings are no longer as well-made. Many have ceded their production to China, and most are simply gone.

If you are interested in acquiring a finely made vintage or antique compass, look for a brand listed below. Make sure it is a bow compass that is rust-free, clean, has no missing parts, and has the capacity to hold a piece of graphite. Many early compasses were made for inking, not graphite. These will not be very useful unless you plan on inking.

Above is a photograph of a precision compass by Rotring, made for inking tiny circles. Many companies who have been known for precision instruments. Of these Rotring was exceptionally good for graphic artists because of their integration with Rapidograph pens, shown above.

- Alvin (Germany)

- Deitzen (USA)

- Fullerton (Germany)

- Gramercy (Germany)

- Haff (Germany)

- Hearthly, made by Intertech (Germany)

- Helix (England, Germany)

- K and E, Keuffel and Esser (Germany)

- Knopf (Germany)

- Koh-I-Noor (USA, Germany)

- Morilla (Germany)

- Omicron (USA)

- Penza Bros. (USA)

- Post (Germany)

- Record (England)

- Ridgway (Germany)

- Riefler (Germany)

- Rotring (USA, Germany)

- Staedler

- Tacro (West Germany)

- Teledyne Post, Fredrick Post (USA)

- VEMCO (USA)