Good and Bad Evolutions

A critical aspect of the TGF Project is that you allow yourself to make small evolutionary changes in your designs over time. This needs to be reflected in the set of finished pieces. The complete set of objects are part of a continuum of design, like a stop-motion animation. You should be able to see what was done to change from the first to the second form; from the second to the third, from the third to the fourth, the fourth to the fifth, and the fifth to the sixth.

What should not happen is that the third, fourth, fifth or sixth looks like it came from the first, or that any shape other than the next in line looks like it came from the preceding one. The complexity compounds on the previous form, until your final object is something you could not have imagined at the outset.

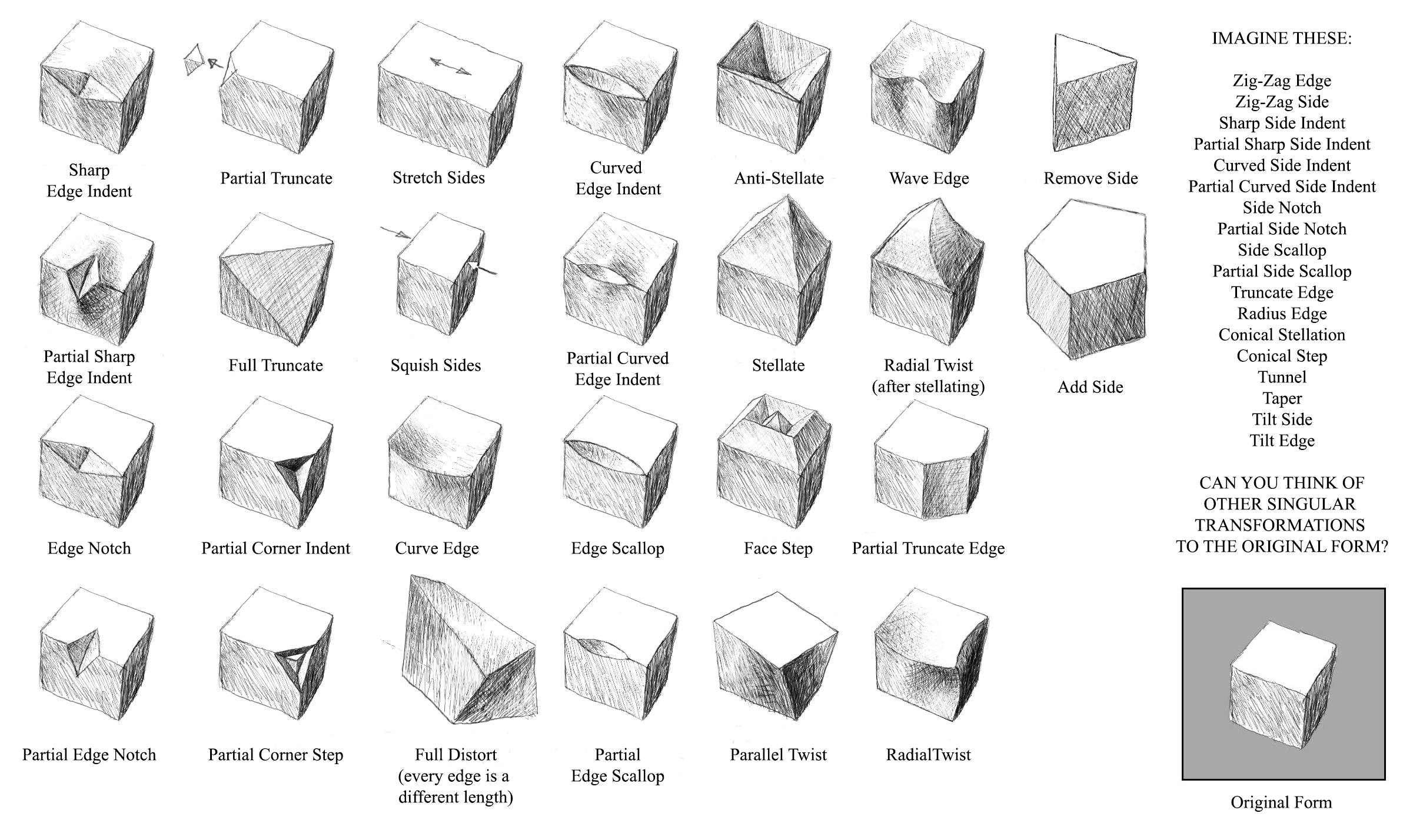

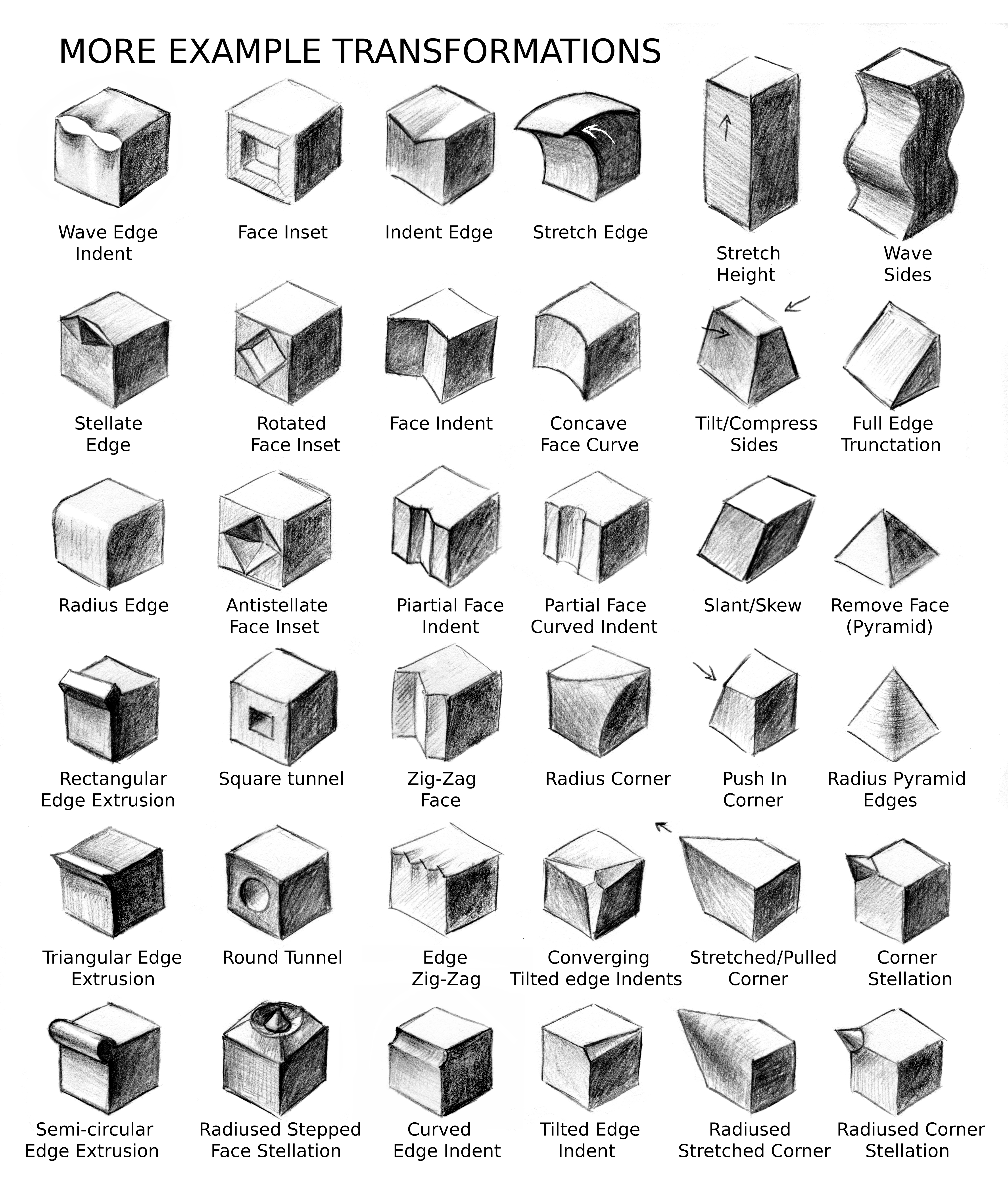

There are probably incalculable sequences and combinations of transformations that will result in infinite branching possible forms, but for now, here are some basic transformations to get you started. Using only these transformations and starting with a simple Platonic solid, it is possible for you to create a completely unique form that no one has ever made before in any class.

You can combine the transformations above into a complex final form by adding a new type of transformation at each step, but it is also easy to choose the easy road, which can result in a lower grade. Below you will find several common mistakes students have made in the past, and ways to avoid them.

Mistake: A Non-Evolving Set

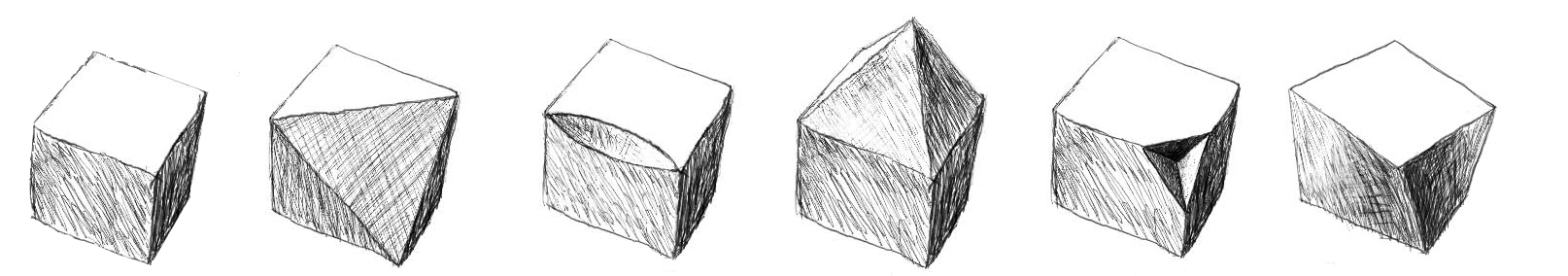

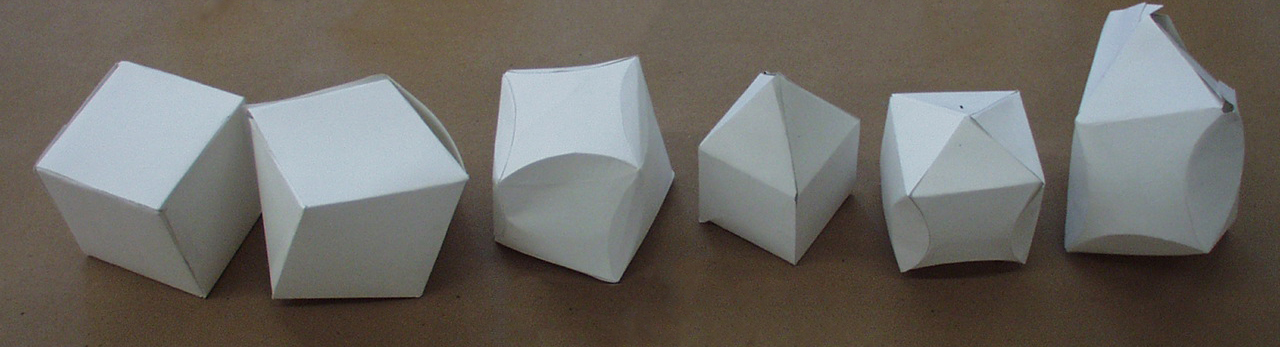

One major mistake people can make is to evolve a bunch of new forms directly off of the first. Here is an example:

Though each object is unique, the third, etc, does not follow logically from their precursors. Instead, they all follow from the first only. This is a "C" project because it does not address the fundamental problem of simple evolution. Also, this is a rather boring set anyway because the maker didn't bother to alter anything more than one part of the form in each step. It would be awarded some points though because there are six neat and well made forms.

Mistake: Too Big a Change (or illogical change)

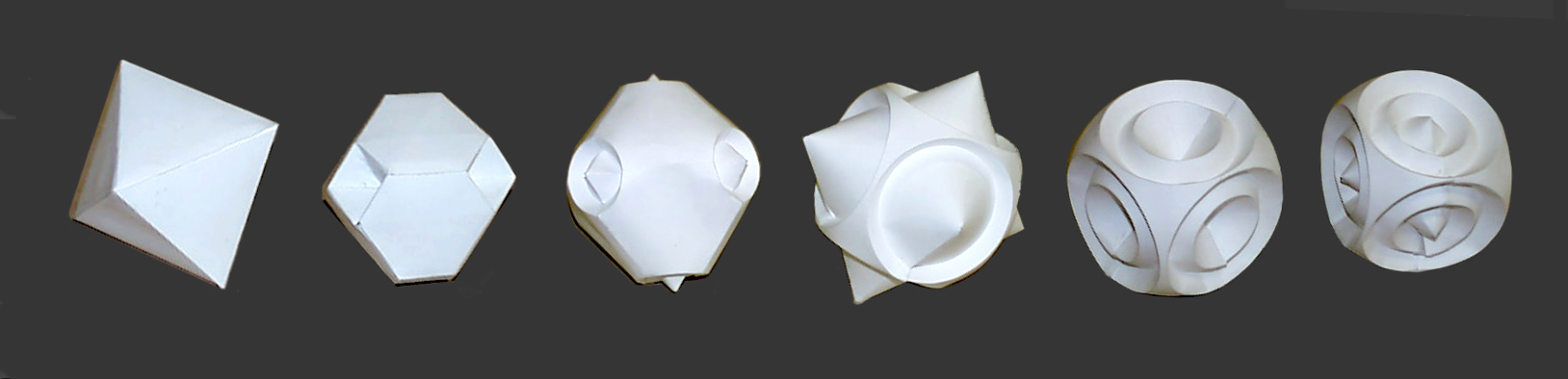

Some sets make a lot of sense, other than one or two pieces. In the example below, it makes sense that the cube becomes twisted. It also makes sense that the twisted cube becomes scalloped.

It does not make sense that the fourth in the series is an untwisted cube with a single stellation; the fourth could have been the second step. While it is alright to simplify in some cases (such as changing a sharp edge indent into a smooth edge indent), this student didn't just simplify, they completely negated the second and third steps. The fifth does make sense coming from the fourth, but it is repeating the scallop. The last one is hard to tell what it is!

On top of not evolving in a logical sequence, the set above is messy and banged up a bit, which contributes to its lower grade.

Mistake: Repeating A Move

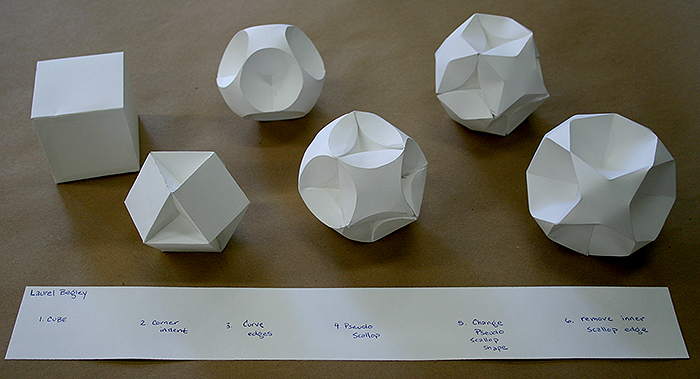

It is not appropriate to repeat a process and treat it like it is a new idea. Below is an example of a beautifully made set that taught the class a lot about craftsmanship and artistry.

This set demonstrates forms evolving smoothly over time. The only flaw in this series is that the last piece repeats the move done in the third piece. However, the project still received high marks because it was so well done, and no one noticed the flaw.

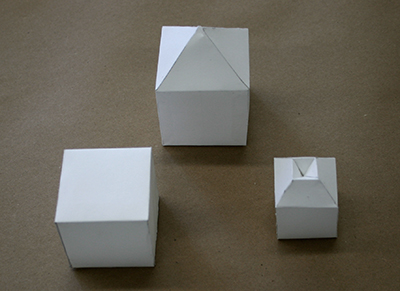

Mistake: Not Enough Pieces

Sometimes a student has good intentions and a belief that they can pull an all-nighter to get things done. Sometimes this works. . . and sometimes not. One of the major reasons a person does not complete a full set is because they were too ambitious. It is good to be ambitious! However, it's also good to learn time management and be realistic about what you're able to complete by the due date.

The set above was evolving nicely. However, the student found that making the fifth one was not easy for her, so she never got finished with the sixth one. The designs are not too complex, so time management could have made a difference. The set received a respectable B grade.

Mistake: Another Incomplete Set, With Serious Problems

The set above is an excellent example of a project that was not taken seriously. The person had no interest in exploring ideas, gaining skills, or solving problems. So the project languished. It is so incomplete that it cannot receive points.

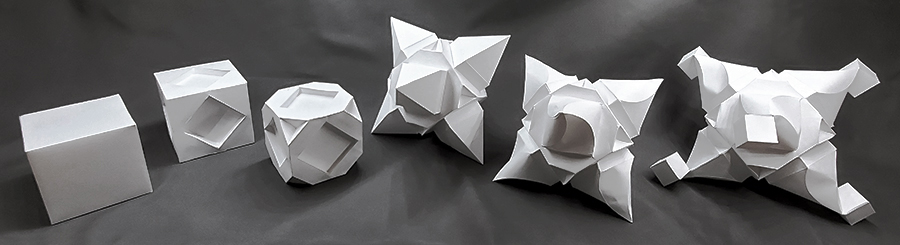

Well Done Examples, and Labeling the Evolutionary Steps of Your Pieces:

When you turn in your TGF Project, you will need to attach a photograph that clearly illustrates the sequential evolution of your pieces. You will be required to list each transformation in order. Note that the three examples below start with the most simple object on the left, and become more complex as they move to the right. Many of the transformations you will attempt will be steps listed in the chart at the top of this page. However, sometimes a student will do a combination of things in one step, or they might do something we have no name for. In those cases, you may come up with a name you think fits, or you may need to become descriptive.

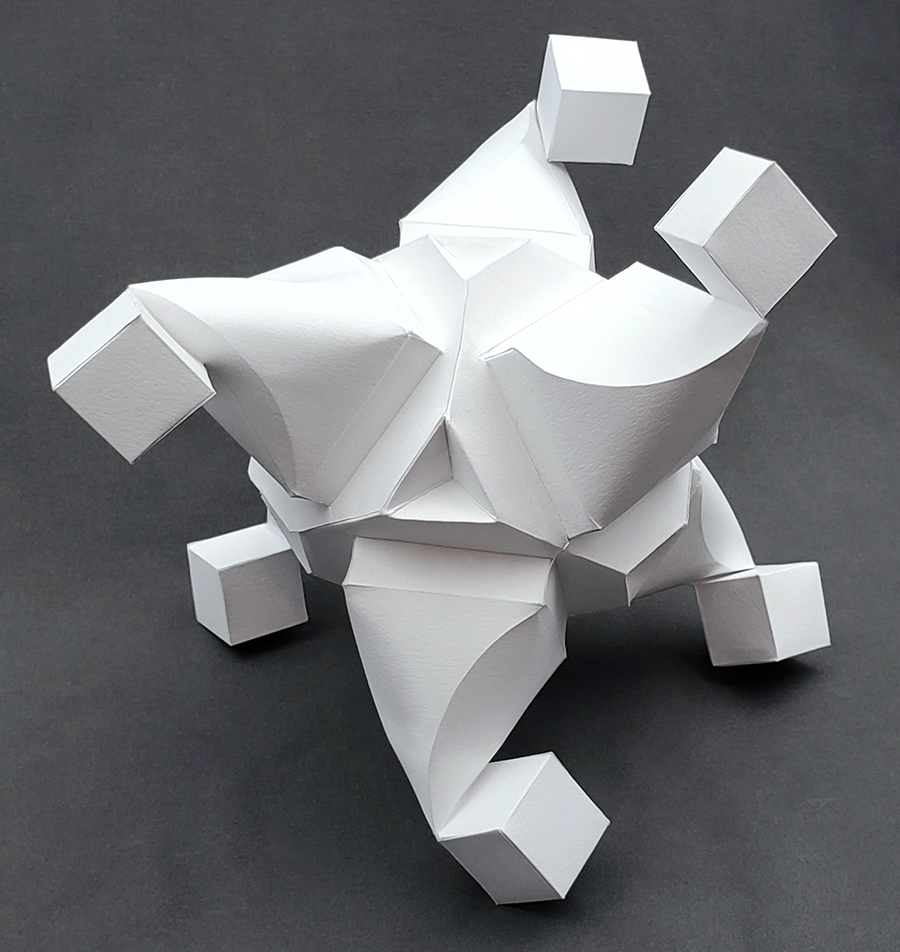

- Cube

- Face indent/deboss (all)

- Corner indent (all)

- Face indent/deboss extrude into full stellation (all)

- Standard stellation to radial twist stellation (all)

- Dimensional cube addition to radial twist stellation tip (all)

Note how Tanya named her final step a "dimensional cube addition." This was a weird transformation she came up with on her own, but the result is beautiful and unique. She also specified that she implemented her transformations uniformly to all sides by including "(all)". This wasn't strictly necessary since she didn't have any asymmetric steps, but if you choose to do bilateral or asymmetrical alterations, it can be helpful to note that.

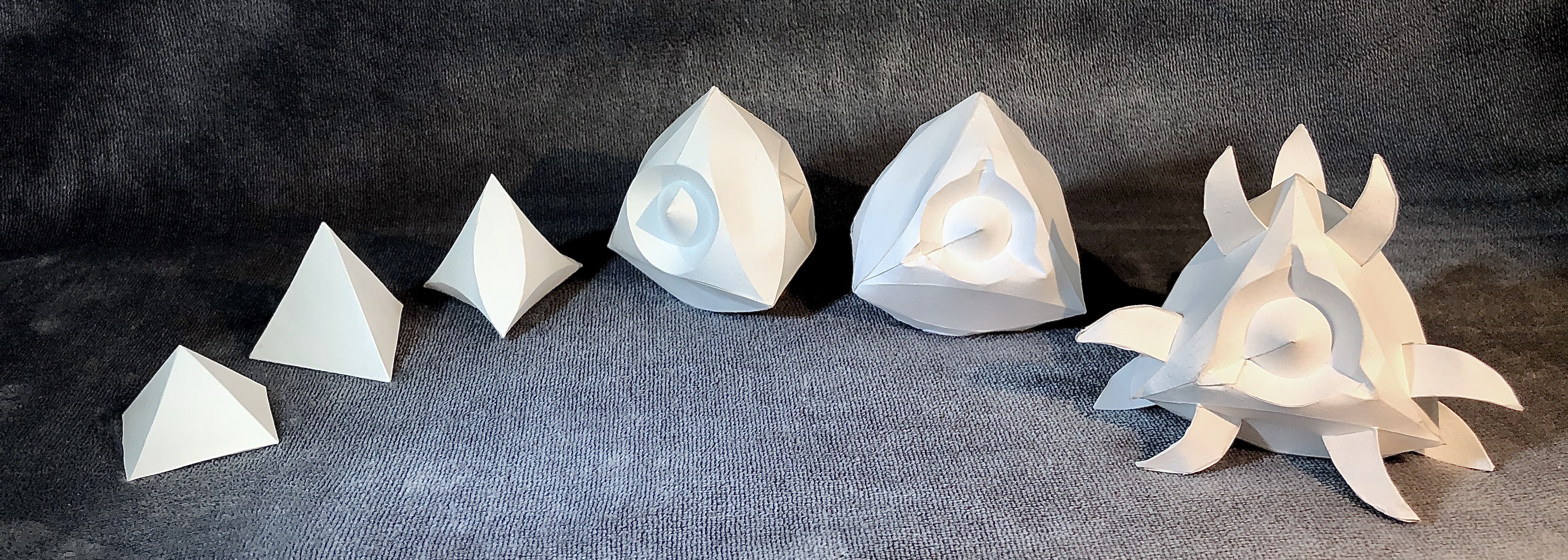

- Pyramid

- Tetrahedron (taking away a side)

- Scalloped edges

- Face step

- Partial edge notch (on the circles)

- Pronged ends

Here is another example where a student came up with her own term for a step since we had no established term for the addition of "pronged ends." Laura started with a very simple transformation as she figured out how to manipulate the patterns, but she ended up with a very complex and striking final form.

- Cube

- Truncate Corner

- Partial Stellate

- Radial Twist

- Corner Step

- Partial Anti-Stellate

Komachi only used terms listed in the chart, but her "partial stellate" is actually much more complex than a normal stellation, since it is offset from the edges of the face that it protrudes from. She was able to use incremental simple steps to arrive at a beautifully complex end product.