About Symmetry

There are many kinds of symmetries in nature, and thus design. The Lamp Project takes advantage of a few types, and allows the repetition of these symmetrical forms to develop a pleasing aesthetic. Here is a list of various symmetries:

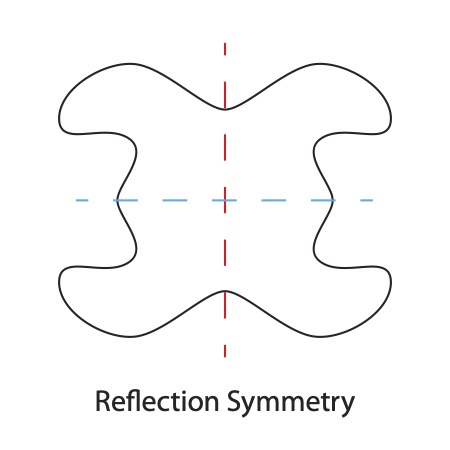

Reflection Symmetry

In order for a shape to have reflection symmetry, there has to be at least one line or plane where the shape can be divided equally, creating a mirror image. One line of reflection is typically present in objects such as chairs, dressers, laptops, and many living forms, humans included.

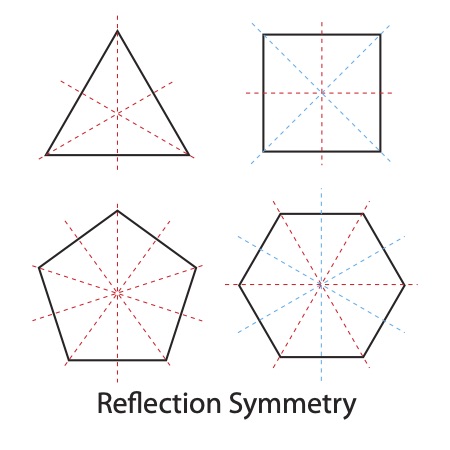

All of the forms shown above, including those representing reflection symmetry, are bilaterally symmetrical. The reflection versions all have multiple lines of symmetry; some of which are identical, and others with two distinct kinds (represented by red and blue). Notice that the regular polygons in the third image have an interesting property: the odd-number polygons have only identical symmetries; the even-number polygons have two types of symmetries.

When an object or shape is symmetrical along a single plane, it is considered bilaterally symmetrical (Bi = "two", Lateral = "side"). There are other forms of reflection symmetry which allow for more than one line of division. An example is a table that may typically have two lines of division: one splitting its long dimension, and the other splitting its short dimension. All of the regular polygons have multiple lines of reflection symmetry; a pentagon having five.

Humans recognize bilateral symmetry innately, it is a basic instinctual behavior. For this reason bilateral symmetry is a powerful design tool. Bilateral symmetry is extremely common in animals and many plants. It physically balances the body gravitationally. Eyes and ears are bilaterally symmetrical, which allows us to understand our position in space, and proximity/directional understanding of other objects. Newborn babies respond immediately to bilateral representations that mimic faces, and imprint on them. People and animals subconsciously direct their attention to bilaterally symmetrical forms.

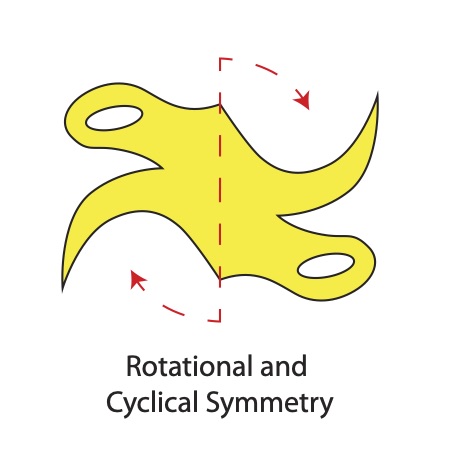

Rotational Symmetry

Rotational symmetry, also known as radial symmetry, requires a radius point where at least one identical copy of a shape is rotated around to make a balanced overall form. As mentioned, all regular polygons have reflection symmetry; they also have rotational symmetry, as does the table described earlier.

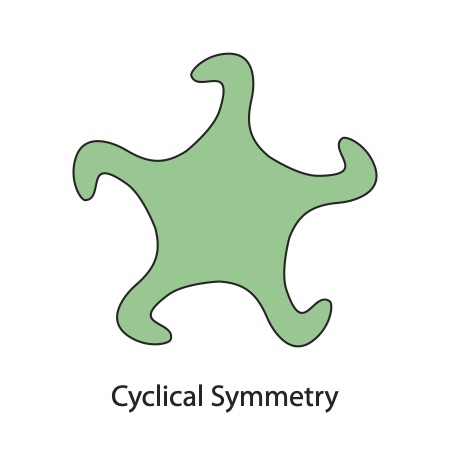

A rotationally symmetrical object can have cyclical symmetry, which means that an asymmetrical element, if repeated regularly about a radius, forms cyclical symmetry. A pinwheel is an example of cyclical symmetry.

On the other hand, if the element of an object has reflection symmetry, and is repeated about an axis, the object has dihedral symmetry (the "di" meaning two, representing the mirror aspect of the element). Interestingly, all regular polygons have reflection, bilateral, rotational (radial), and dihedral symmetry!

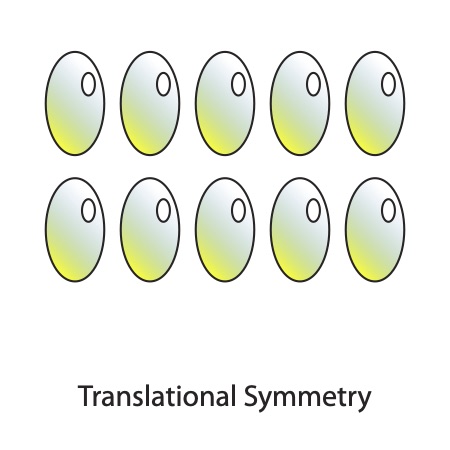

Translational Symmetry

When an object is repeated in a row or grid, it follows translational symmetry. The basic form itself does not need to be symmetrical. Fabrics, wrapping paper and wallpaper often utilize translational symmetry because it is both an efficient method of applying a graphic element, and visually stimulating.

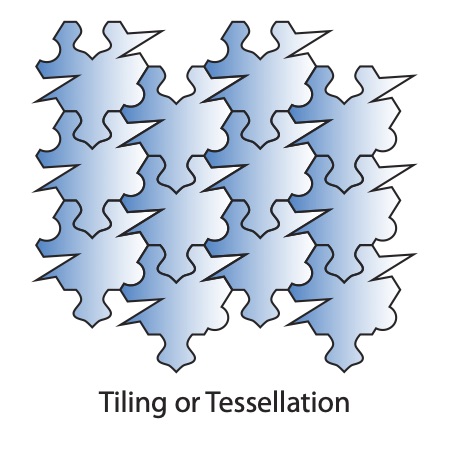

If the translation also locks together in such a way that its forms completely touch their repeated selves with no gaps or overlaps, it is considered tiling or a tessellation. Examples would include much of the work of MC Escher, and is especially present in Islamic tile patterns.

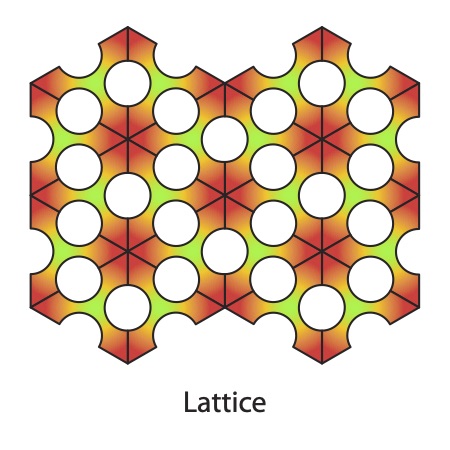

If the translation is interlocked in some way, but with gaps, it is considered a lattice. Chain mail is a lattice.

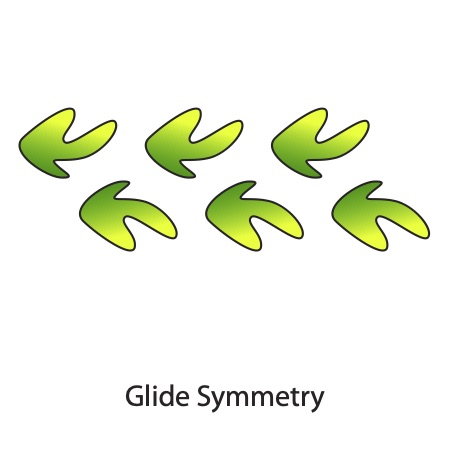

Glide Symmetry

Glide symmetry is when an object is translated in such a way that there is a mirror axis to the translation, and where the objects are offset in that mirror translation. An example is footprints in the sand. There is reflection symmetry, offset in a stepped pattern. It would not be considered glide symmetry if the pattern is not also offset. If one were to hop along the sand, there would be mirror symmetry and also translational symmetry, but not glide symmetry. Glide symmetry exists in many plants that have leaves or branches that grow out to the left and right in an alternating pattern.

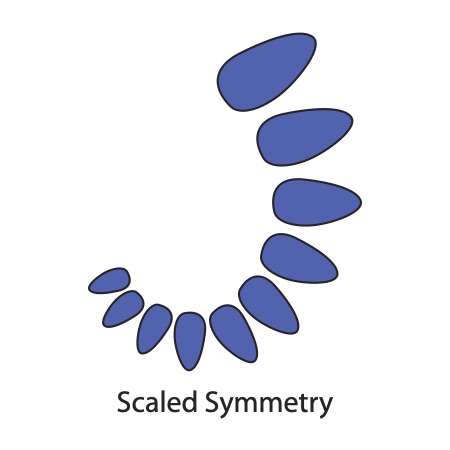

Scaled Symmetry

When an object is repeated while also proportionally changing in size, it has scaled symmetry. As with translational symmetry, the object itself does not have to be symmetrical. The symmetry is created by repetition. Scaled symmetry is often found in nature, and can be seen in pinecones and spiral shells. Many leaf groups have scaled symmetry, such as on the Ash tree. Leaves in general are typically composed of elements that overall have scaled, mirrored and translational symmetries; some also exhibiting glide symmetry. The golden ratio generates a scaled symmetry of perfectly repeating, proportionally identical rectangles, triangles, and other forms. Many insects grow in such a way that their youngest versions look identical to their mature versions, except for their scale.

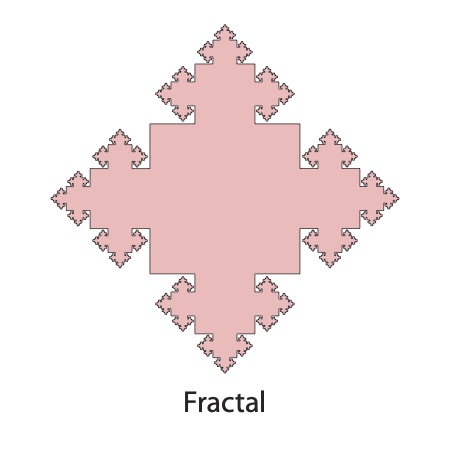

A fractal is a type of scaled symmetry where no matter how zoomed in you go, the form appears the same. The fractal example, above, was created by drawing a square, followed by squares on each side 40% smaller, over and over and over; every edge has a smaller square growing from it, forever. The result is that a pure mathematical fractal has an infinite perimeter length. Of course, that can never be achieved in the physical world. The fractal shown above also has bilateral, reflection, and dihedral symmetry.

From a mathematical point of view, symmetry means that a form exactly repeats. In a practical sense, no physical object is perfectly identical; thus nothing physical is truly mathematically symmetrical.