Making Paper Prototypes

The Lamp Project requires the creation of three unique prototypes, each demonstrating different concepts: Static, Dynamic, and Circumvolution. These are achieved through sketching and physical construction of paper models. The models need to be made from enough modules to demonstrate the various extension interactions present in the design.

Here is a list of typical angles that show the different extension interactions:

- Vertex - The point where three or more planes meet in a peak.

- Edge (Dihedral Angle) - Where two planes intersect and the extensions hook together and pass by one another.

- Polygon Face - The view of a plane from straight on, where the extensions run towards each other.

- Sometimes there are multiples, or more interactions than those listed above that must be considered. This is the case with many Johnson Solids.

There is also a view of the design that is not about symmetry. Instead, it is a random, angular view that shows the asymmetry of the design when seen not from a straight-on view from a polygon, edge, or vertex.

Above are four prototypes, made from paper. The one on the left is a simple static design. The one on the bottom is also static, but more visually complex with many cutouts. The one on the right is dynamic and begins to have a rotational movement, and resembles paperclips. The top prototype demonstrates circumvolution, though to minor effect. The elephant theme has a rotational effect, and the trunks of each elephant link to the leg of the one in front of it.

Notice that each design utilizes a dodecahedron volume, and that only six out of twelve modules are required to demonstrate all types of symmetries. It is important to understand that your prototypes DO NOT all have to utilize the same underlying polyhedra or polygons. In this case, the student did use the same underlying forms, but one could just as readily design one prototype using the dodecahedron, another an icosahedron, and another a truncated cube.

How Many Modules for a Prototype

In the prototype stage, you do not need to make a fully enclosed model. You only need to make enough test modules to demonstrate all of the various symmetries. However, for the best understanding of your design, making at least half of the volume will help you understand what the overall form will look like. For an Octahedron you'd need at least 5 of the 8 modules to demonstrate the symmetries. For a dodecaherdon, you'd need 6 of 12 modules. For an icosahedron you'd need 6 as well, but 10-15 would look much better and complete.

Prototype Scale

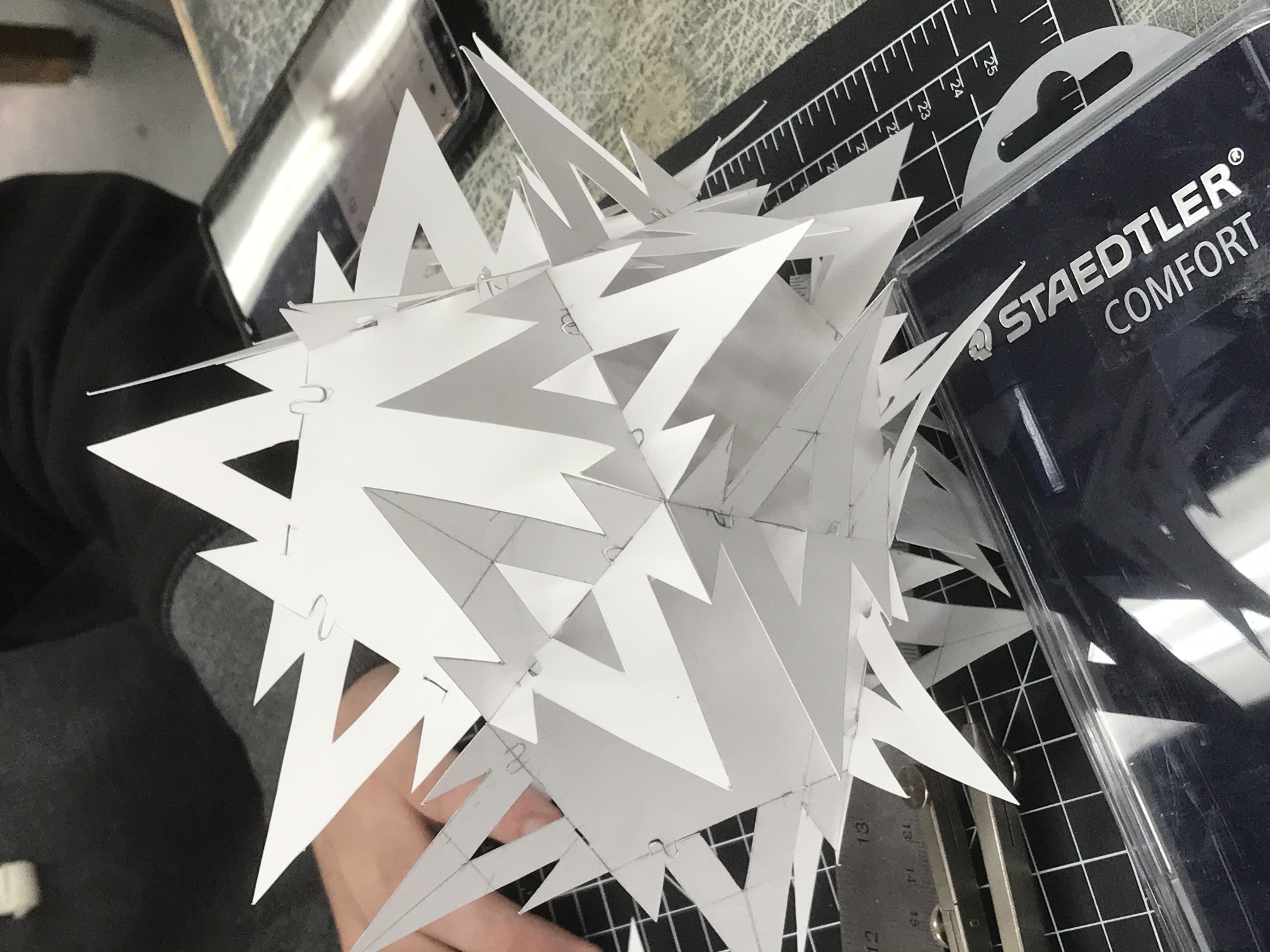

The small prototype, above, is seen from its vertex, where vertex symmetry is easily demonstrated. The pitch angle of each extension matches the angles of the base pentagon. This makes the extension's edges run close to one-another as they project out.

Also easily seen in this photo is the dihedral symmetry. What is not well demonstrated is the overlapping symmetry that occurs above the base pentagon.

The size of this prototype is pretty small. A prototype does not have to match the size of the final piece. If this design was chosen for the real lamp, the module template would have to be enlarged enough for the lamp to accommodate the socket and LED bulb. It is useful to make a prototype actual size, but in order to save on materials, it is not essential.

Two or More Module Shapes in One Design

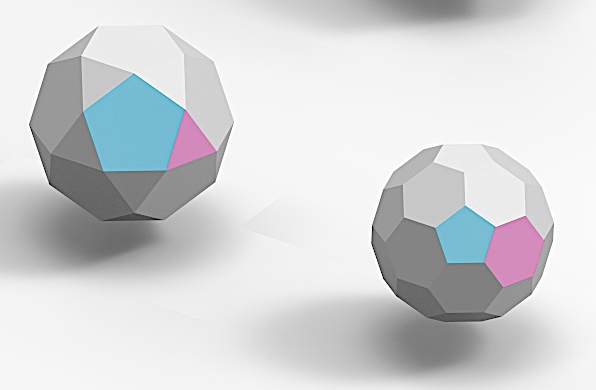

Any prototype that has more than one type of polygon requires multiple module designs. This must be demonstrated in your prototype. For example, a truncated cube would need two distinct modules: a triangle and a square. An icosadodecahedron would need hexagons and pentagons.

When a prototype is based upon a truncated volume, it will require the design of two distinct modules. The extensions of these modules can all be the same, though not absolutely required. If they are, however, dihedral symmetry is achieved. Notice that all edges of all polygons in the above truncated dodecahedron are of equal length. There are twelve pentagons and twenty triangles here. That makes a total of 120 edges, or 60 dihedral angles.

The truncated design allows for an easy solution to the Butterfly Problem, described at the bottom of the introduction page. This is because the triangles' edges only touch pentagons and the pentagons' edges only touch triangles. In the sketch, notice that the pentagons have arrows rotating counter-clockwise, and the triangles have arrows rotating clockwise. At the dihedral angles, both the triangle's and pentagon's arrows move in the same direction. This means that extensions can be designed to be bilaterally symmetrical along the dihedral axis, with mirrored symmetry rather than the typical rotational symmetry.